from the current 400 million, and Asia will see

a 61 percent rise.

THE OTHER SIDE OF URBANIZATION

A large proportion of the global urban

population will reside in informal cities or

settlements like the favelas in Rio de Janeiro.

Bettencourt says cities address this problem

by improving streets, accesses, buildings

and infrastructure in these neighborhoods

or relocating people. ”France and UK are

typical examples of often unsuccessful public

housing; it created several vertical slums on

the outskirts of Paris and parts of London

that over time caused many socioeconomic

problems – it is crucial not only to build

housing, but also understand how it ’runs’

socioeconomically – this has been done

better in places such as Hong Kong or

Singapore,” explains Bettencourt.

A 2014 report titled “Human Development

in South Asia, Urbanization: Challenges

and Opportunities” makes some key

observations. In the past three decades,

Bangladesh witnessed the highest rate of

urbanization (4.19%) in South Asia, leaving

behind populous countries like India

(2.87%), and Pakistan (3.41%), but 60% of

its population resides in slums and 21% of

its urban populace lives below poverty line.

The report blames “unplanned” urbanization

for inadequacies in infrastructure, public

transportation, housing, water and

sanitation, energy, solid waste management,

and health and education among others.

”Issues that require less physical intervention

are easier to resolve than those that need

extensive physical planning and construction,”

points out Bettencourt. Take Mumbai for

instance, he says. ”The state is licensing an

increasing number of tall buildings, but many

of them don’t have integrated sewage and

regular water supply because that requires a

lot of physical work – digging, laying pipes,

etc. – but other things like electricity or

telecommunications are much easier, so you

find them even in poor neighborhoods,” he

adds, highlighting the contrast.

CROSSING BOUNDARIES

As cities expand across boundaries and

spill over multiple jurisdictions, Bettencourt

says they gather more complex political,

municipal and bureaucratic undertones,

which means it takes concerted efforts from

various stakeholders to design a spatially

integrated city with appropriate linkages. He

cites the example of Medellín in Colombia,

a city in a mountainous valley, which links

its varied neighborhoods using public

transportation like cable cars and metros.

“It’s a system where the thinking is to

improve and create a city that is more

socially connected,” he notes. European

cities, such as Frankfurt and Rotterdam, and

some American cities, such as Boston or

Portland, have made their mark in building

efficient systems. Southeast Asia’s island

country Singapore is another case in point. Its

ambient living environment with parks and

gardens around concentrated mini townships,

its wastewater treatment initiatives (which

meet 30 percent of the city’s water needs)

feature

feature

and excellent connections via metro and

bus systems make the modern city-state

sustainable.

To establish an integrated view of

development, some cities are also exploring

participatory design, which extends to

involve local communities. ”People who live

in cities they can feel proud of feel greater

ownership of it, identify with it, become more

interested in the outcome and work toward

improving their own living environments,”

says Woo. ”Adopting participatory design is a

step toward improved urban development,”

she points out.

THE SMARTER WAY OUT?

Emerging economies in Asia Pacific and Africa

are taking it a step forward and making huge

investments in creating integrated cities often

dubbed as “smart” cities.

”It’s primarily an engineering concept

about how to use data to run a better and

more integrated operation, and I think it can

be an enabler of better city government in

terms of service delivery,” says Bettencourt.

A recent report by Navigant Research notes

that the cumulative investment in smart city

technology in Asia Pacific will total $63.4

billion during the period from 2014 to 2023.

While Songdo in South Korea, Fujisawa

in Japan, and Iskandar in Malaysia are

prominent examples, India’s upcoming 100

smart cities, South Africa’s $7.4 billion smart

city Modderfontein, and Kigamboni, outside

Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, are all gaining

popularity.

Since cities, by nature, are constantly

changing, developing countries that build

cities swiftly have to be cautious. China,

says Bettencourt, is rapidly building cities,

highways, high rises, affordable homes and

industrial zones. ”It’s like big cities that come

out of a machine, which in the long run,

may not do very well – at least it didn’t in the

West,” he warns. The Chinese government is

taking steps to adopt a new mechanism. Last

year, it announced a renewed urbanization

plan (2014–2020), which aims to be more

people-centric and embraces sustainable city

management.

SUSTAINABLY YOURS!

After all, it is a matter of choice. ”There are

different ways of making cities livable, and

several of those ways are sustainable and

others are not,” adds Woo. The onus then

is on every country to understand its urban

environments, find sustainable solutions

within its own contexts and build cities that

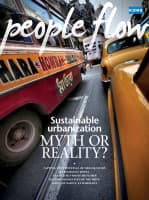

will stand the test of time. Clearly, boarding

a local train in Mumbai seems easier in

comparison. /

“Issues that

require less

physical

intervention are

easier to resolve

than those that

need physical

planning.”

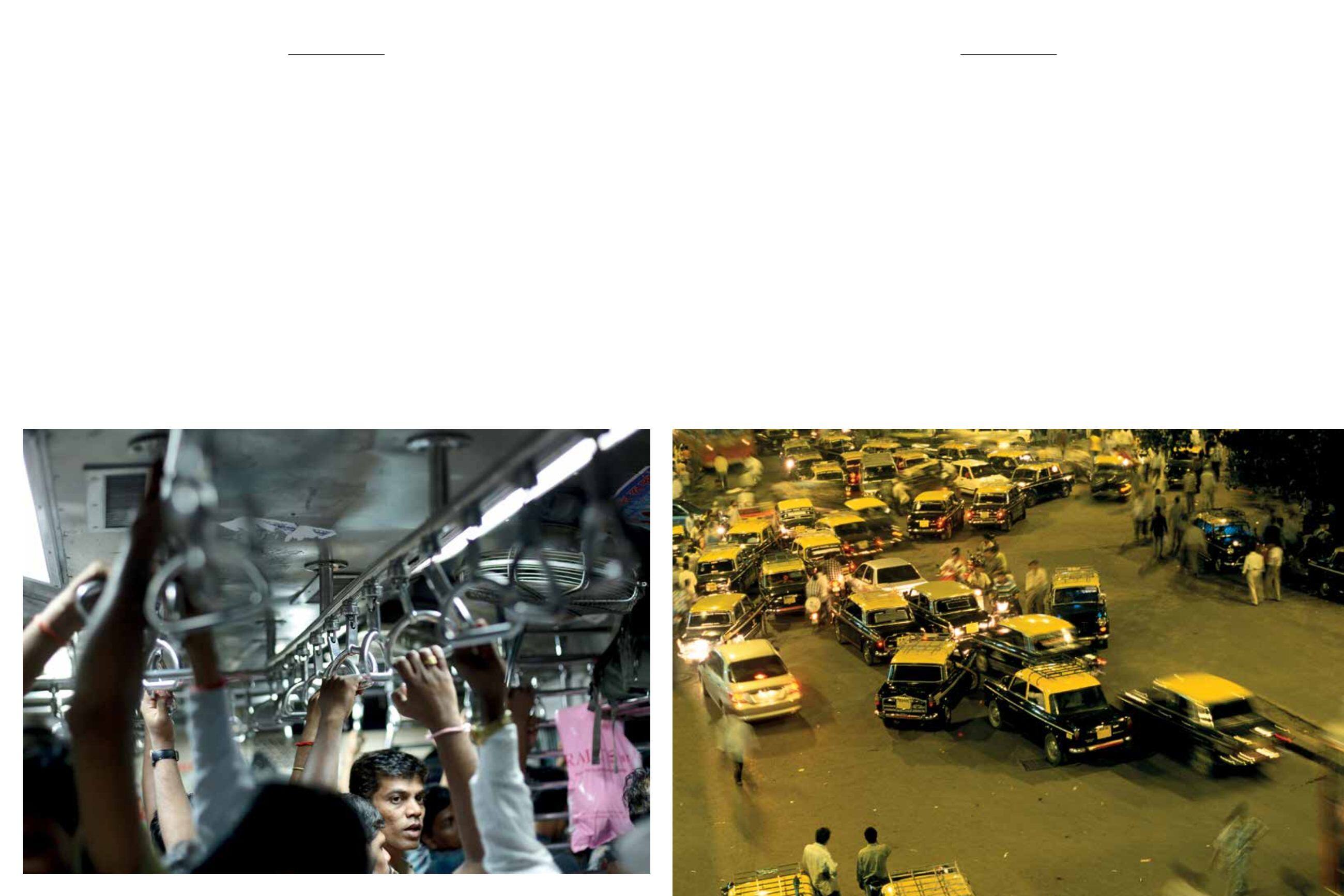

Traffic on the roads

of Mumbai, India.

7.5 million

commuters in

Mumbai use rail

services every day.

6

7